100 Years, 100 Stories

Hannah Wise

Virginia Mason Seattle

“I started working for Virginia Mason in the Ophthalmology department in March 2017. In less than six weeks, I became a patient myself and saw all the ins and outs of the hospital. For six months prior to that, I had a persistent cough that started when I was eight months pregnant with my daughter. I was told then that I had acid reflux, which was causing my cough. My symptoms improved after my daughter was born, but by April the cough returned with a vengeance. In late April 2017, my cough had become so bad that I was coughing up blood. By 4 pm, I thought I should see someone before I went home. I took the elevator up to General Internal Medicine and asked if any provider could see me. A triage nurse brought me into a room and I showed her the pictures of the blood I had expelled. She sent me straight to the Emergency Department and did not let me talk her out of it. I walked myself to Jones Level 7 and they immediately got me in for a CT scan. I was diagnosed with a carcinoid tumor that was completely occluding my left lung. I was an otherwise healthy 26-year-old so this came completely out of left field. I was admitted and the next day I met Dr. Hubka, who later removed the tumor and did my partial lobectomy a few months later. I was already impressed by Virginia Mason’s reputation, which is what attracted me to the job. But after becoming a patient myself, I am so proud to be a part of this amazing organization that is saving lives, mine included.”

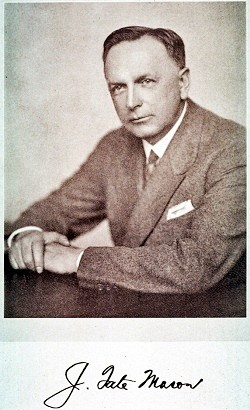

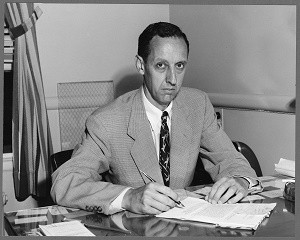

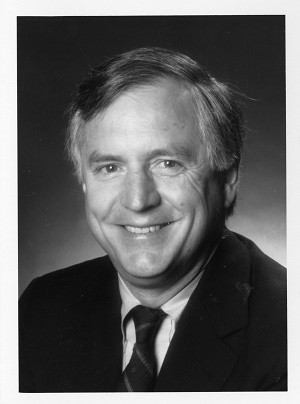

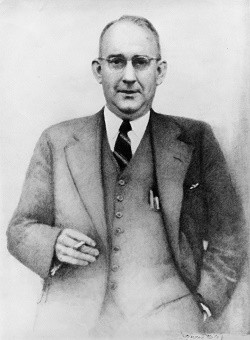

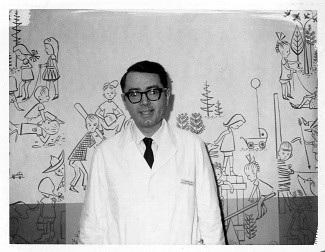

Virginia Mason Co-founder James Tate Mason Sr., MD

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

Dr. Mason was born May 20, 1882 in Lahore, Va., the son of a physician who had served the Confederacy under Stonewall Jackson. His mother was the daughter of a prominent Virginia colonial family. At 14, he entered the Locust-vale Military Academy, where he distinguished himself more on the baseball field than in the classroom. In 1901, he entered the University of Virginia Medical School and graduated in 1905 as one of the most popular students in his class. After medical school, he spent two years at the Philadelphia Polyclinic (the post-graduate school of the University of Pennsylvania) followed by serving as a resident at the Municipal Hospital of Philadelphia for the treatment of contagious diseases. In 1907, with his internships completed, he signed on as a ship’s surgeon aboard a steamship bound for Seattle by way of Cape Horn. The position offered $100 and a return railroad ticket home. However, he never used the ticket home. Arriving in Seattle in mid-summer with $50, he liked what he saw of the Pacific Northwest and, within two weeks, was hired as company surgeon – at the age of 25 – for a coal company in Black Diamond, Wash. In 1909, he returned to Seattle to practice there. Within a few months, he welcomed the opportunity to become physician to the county jail. He was married in 1911 and in 1913 he and his wife, Laura, welcomed the first of their three children. In the next few years, Dr. Mason earned the respect of his patients as well as the city’s business and political leaders. He was elected coroner of King County and organized an Anatomical Club with his colleagues, which later merged with the Seattle Surgical Society. From 1917 to 1920, he was superintendent and surgeon of the King County Hospital. And in 1917, he organized a partnership with five doctors and two associates to form the Mason-Blackford-Dwyer Clinic, which would eventually become Virginia Mason Medical Center.

James Tate Mason Sr., MD

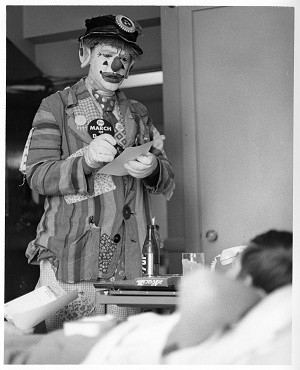

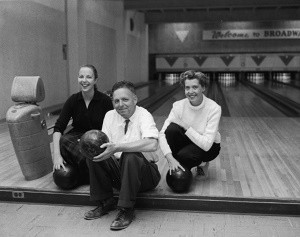

Seattle TV Icon, J. P. Patches, Visited Virginia Mason in 1970

Julius Pierpont “J. P.” Patches was a clown and the main character on The J. P. Patches Show, an Emmy Award-winning local children’s television show on Seattle station KIRO TV, which was produced from 1958 to 1981. J. P. Patches was played by show creator and Seattle children’s entertainer, Chris Wedes (1928-2012). When the show ended in 1981, The J. P. Patches Show was one of the longest-running, locally produced children’s TV programs in the United States.

In 1970, J. P. Patches visited Virginia Mason as part of the team member recognition program, PRIDE (Professional Results In Daily Effort). That year, Patches emceed the staff “Hobby Show” competition. Patches also visited with young patients in the hospital to provide laughter and encouragement.

JP Patches brightens the day of a young patient at Virginia Mason in 1970.

Fred Savaglio

Virginia Mason Seattle

“I have a lot of stories about wonderful experiences at Virginia Mason. As an example, a very moving story was in the aftermath of the Hudson Arms fire when the six or seven evacuated residents were gazing up at the apartments they could not return to. Among them were three who owned cats which, at that time, may have been lost during the fire or fire department operations. Eventually, we were able to gain permission for Virginia Mason engineers to go in and look for the cats. About 45 minutes later, the three engineers came out and each was holding an agitated cat. The residents were emotionally drained and a lot of tears flowed. A second memorable story that night was when the residents were being processed by the Red Cross to shelters where they would remain until other more permanent housing could be found. Prior to the Red Cross transport, it became known that each resident had medications they would need that night. Nancy Hendler was on scene and she patiently took each resident’s medical history and with her Nurse Practitioner’s prescriptive authority wrote all the scripts they would need for the coming days. The Red Cross then went out got those prescriptions filled. So, many times Virginia Mason staff have stood strong in tough situations. I think of so many unsung heroes and heroines. Although their names have long left my memory, I was very moved each time team members came through. These are a couple of the fond memories about Virginia Mason that I wanted to share.”

John Dare: Mason Clinic, Virginia Mason Hospital Administrator 1935-1977

(Excerpted from an interview by William Steenrod Jr., MD, on Oct. 11, 1985)

John Dare was an administrator in The Mason Clinic and Virginia Mason Hospital from 1935 to 1977. His father was Lewis Dare, the first administrator.

“I went to the University of Washington and graduated in business administration. Eddie Carlson* was a classmate. He was broke. We were all broke. There weren’t any jobs around. Eddie had to quit school and went to work for Western Hotels. Most of the guys graduating were going home to live with their parents because there weren’t any jobs in sight. Believe me, it was bleak.

One day, Eddie called and said, “I think there’s a job down here at the Roosevelt Hotel. Come down and get here quick. I got the job as a night auditor for Western Hotels at the Roosevelt Hotel. Eddie was a room clerk and we worked there for 18 months together. He then took off and went up to run the President Hotel in Mount Vernon, which was his first command in the hotel business.

About the same time in 1935, I got a call from Dr. Tate Mason who said, ‘I want to talk with you.’ It came as a great surprise. But having nothing else to do, I came up the hill and talked with Dr. Mason and my father. They had decided that due to the growth of the Mason Clinic and Virginia Mason Hospital, they wanted to put another guy into the organization with a business background.

A few days later, they called me and told me if I wanted to the leave the hotel business, I could come up here and learn this racket. I came up the day after Labor Day 1935.”

(* Leader in the hospitality industry, driving force behind the Century 21 World’s Fair, and CEO of United Airlines.)

Gigi Gempesaw, RN: Director, Acute Care Services

Gigi Gempesaw, RN, started work in a Virginia Mason pharmacy as a nursing student 34 years ago. She remembers delivering medications to hospital rooms and observing the patient-nurse relationship. The one-to-one interaction struck her as extraordinary.

“I decided then that I wanted to be that person making a connection with the patient,” said Gempesaw. “As nurses, we’re given the gift of being there at someone’s most vulnerable time.”

She remembers working in different organizations as a nursing student, but none felt as welcoming to her as Virginia Mason. Encouraged by a sense of inclusiveness and respect among team members and leaders alike, Gempesaw knew she would have the foundation to take good care of patients. Today, no matter who she calls on during the work day, she knows their commitment to the patient is equal to her own.

For Gempesaw, it all comes back to valuing relationships, with patients and team members. Couple that with a healthy resiliency, and you will have what it takes to thrive as a nurse.

“Whether you work somewhere for three days or 30 years, make those connections,” she said. “If you’re the nurse helping a patient at 2 a.m., it’s a moment they may always remember. I can’t imagine another profession that would bring the same joy to my life.”

Gigi Gempesaw, RN: Director, Acute Care Services

Anna J. Fraser, RN – First hospital and nursing service superintendent

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

Anna Fraser, RN, graduated from Saint Joseph’s School of Nursing in Tacoma. She worked for Dr. James Tate Mason in 1918 and joined him and his associates when Virginia Mason Hospital was founded in 1920. She held the position of superintendent of the hospital and nursing service until her retirement in 1944.

It was a proud Fraser who enrolled three students in the Virginia Mason Hospital School of Nursing in 1921 and made arrangements for their graduation on May 7, 1925. Each succeeding year, the graduating class increased in size.

Fraser was referred to as a superintendent of nurses who guided with tenacity of purpose and disciplined a modest (nursing) family of her own.

In 1929, students were first taught by professors from Seattle College and in 1936 the Student Body Association was organized. The first capping ceremony for students of the Virginia Mason Hospital School of Nursing was held in January 1938. In 1946, the ceremony moved to Blackford Hall and continued every year until the training program combined with the baccalaureate nursing program at the University of Washington School of Nursing in 1957.

Fraser was loved and admired by the students. After a 26-year career at Virginia Mason, she retired from the well-organized and fast developing nursing training school and growing, 150-bed hospital.

In appreciation for her countless contributions to the training program, the school library was named in her honor by the alumnae and students in May 1950.

Charleen Tachibana, Senior VP, CNO: When a Calling Becomes a Call to Action

Every day Charleen Tachibana, RN, works to keeps nurses at the bedsides of patients. It’s a basic idea that has required a career’s worth of passion and innovation. It called for implementing a care management system never tried in a health care setting. And it produced outstanding results in patient health and safety, efficient practices and personal care time for patients.

Since starting as a student nurse at Virginia Mason in 1976, Tachibana has embraced new learning opportunities at every turn, committing herself to the development of nurses in leadership. In recognition of her vision and accomplishments in advancing clinical care, Charleen was honored as a Fellow by the American Academy of Nursing in 2012.

“Charleen’s experiences as a nurse at the bedside give her an invaluable perspective as a transformative leader,” said Sarah Patterson, executive director, Virginia Mason Institute. “Charleen is one of those rare leaders who is at ease talking and thinking in terms of the systems of care, but is also able to understand and articulate the impact of a decision on the individual patient.”

Guide. Mentor. Visionary. The consummate caring professional. Inspirational. A force for change. These are some of the words Charleen’s colleagues use to describe her. Tachibana has said the best part about nursing is making a difference in peoples’ lives. But she also finds great fulfillment in the teamwork and sense of shared purpose at Virginia Mason.

“Having worked with Charleen since the day I arrived at Virginia Mason in 1978, I have been able to watch her develop from a superb cardiac and critical care nurse to an exceptional leader and administrator,” said Gary S. Kaplan, MD, chairman and CEO, Virginia Mason Health System. “She combines the very best of nursing practice with the vision, caring and passion to truly transform health care.”

Team Member-Supported Charity Auctions in the ’80s and ’90s

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

“The medical center’s team member Sweet Charity Auction was started in 1984 to raise additional funds to help care for patients in need. In 10 years, team members raised more than $350,000. Janet Walthew from the business office provided the spark and leadership and identified a group of very committed team members to make it work.

“At one auction, the fire department arrived when Bob Weissman, MD, was demonstrating a chainsaw and accidently set off the hospital’s fire alarm system. (The item he was auctioning was a vasectomy.) On another occasion, Bill Traverso, MD, brought his llamas for a petting zoo at the entrance of the hospital, which was a traffic stopper. And at a different auction, part of Terry Avenue was closed for a daytime “Western Street Dance,” which was also a great morale booster.”

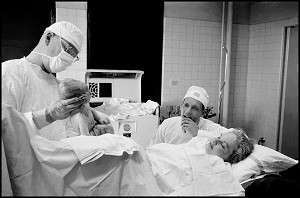

One of the First Hospitals in the U.S. to Allow Fathers in Delivery Rooms

(Excerpted from ‘Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995’)

“In the 1940s and 1950s, innovations in medicine were rapidly occurring throughout the country. One controversial innovation was the move to permit fathers to enter delivery rooms and participate in the birthing process. This was a decision that was widely criticized by some who thought it would be risky for the father – who might interrupt things by fainting – and delivering mother.

‘After all,’ opponents said, ‘we are there to take care of the mother and child, not worry about the husband.’

“In the late 1940s, Virginia Mason became one of first hospitals in the nation to allow fathers in the delivery room. Leadership for the change came from Robert Rutherford, MD, a member of the visiting staff.

“In 1955, LIFE magazine published a related story, which included a photo of a father in a delivery room at Virginia Mason.”

©Burt Glinn / Magnum Photos One of the First Hospitals in the U.S. to Allow Fathers in Delivery Rooms

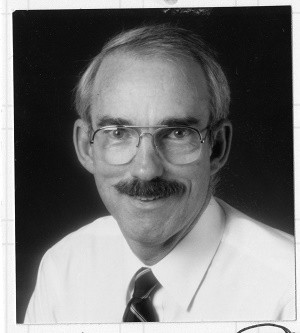

Jim Benson, MD: Practiced at Virginia Mason Starting in 1975

(Excerpted from an interview by John Kirkpatrick, MD, on Sept. 24, 2015)

“Soon after Dr. Paul Fredlund arrived here, he recruited me, which was pretty nice given the fact that there was no position. The Department of Endocrinology and Medicine was kind enough to create a position that didn’t exist. So, we were loaded with endocrinologists at that point, which was a lot of fun. One of the advantages of being collaborative and collegial in the department was that your experience expanded exponentially. At the end of a week when I hadn’t seen many interesting cases or pathology personally, I would realize that I’d seen a bunch of great cases. Because someone would grab me out of a room and say, ‘What do you think we ought to do about this complicated case?’

“The highlight of my career at Virginia Mason was when we did a bunch of research on the insulin pump about 1985. Drs. Bill Camberlane and Bob Sherwin at Yale thought there should be a better way to deliver insulin than by injection twice a day. They literally dusted off a chemotherapy unit or infusion system and said, ‘We ought to toy with this thing and see if it’ll work.’ It was called the blue brick. You had to change the basal rates with a screwdriver. They did their first six and reported a dramatic improvement.

“So, we thought this is something we should get interested in. We toyed with the idea of flying back to Yale, but they were out here for a meeting. Dr. Sherwin said, ‘There’s really nothing to it. I can call you or write you with the protocol on how to dilute the insulin and how we calculate the basal rates. You guys can do it.’ We each got one blue brick from the manufacturer and one patient each and tried it out. We were impressed and adopted it whole-hog.

“One of the highlights of my academic career was about a year later. We were invited back to Minnesota to a company meeting to present everybody’s experiences and suggestions for new pumps. I was nominated by the department to represent us. I showed up late, got up the next morning and realized that people there were all the big names in diabetes. These were heads of departments, people I’d been reading about for years and there was me.

“I got up and said, ‘I’m from Virginia Mason Clinic and am here to report on our first 100 cases.’ There was a visible gulp from the crowd because we had taken it on full-speed. That led to two articles in the New England Journal authored by Dr. Bob Mecklenburg, which featured all of us. I thought that was pretty inspiring!

“Another unique aspect about Virginia Mason back in those days was that surgical residents rotated on the medicine service and medical residents rotated on the surgical service. Everybody knew everybody and we all got along well. Before there was a pyramid with the patient at the top, we already knew that. Competition between surgeons and medical people didn’t make sense. What made sense was taking care of patients. I think that interaction among different services was highly valuable.”

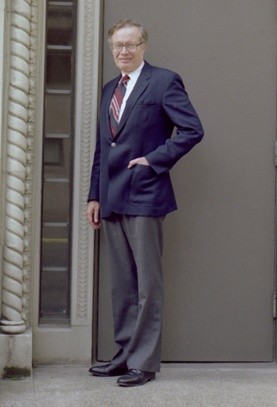

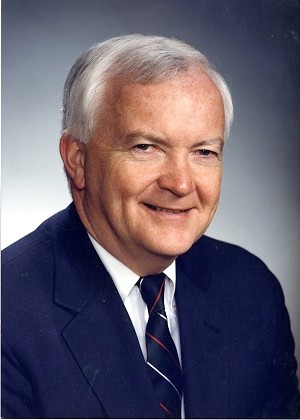

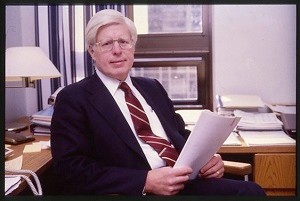

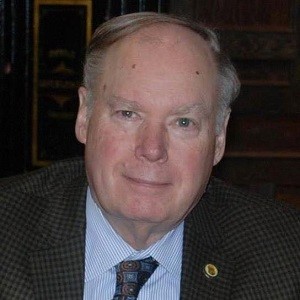

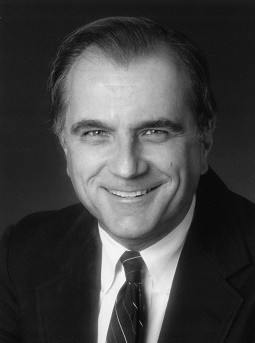

Austin Ross (1929-2020): Longtime Influential Leader at Virginia Mason

Austin Ross joined Virginia Mason Hospital in 1955 as the organization’s first administrative resident and retired in 1991 as executive administrator. Over his 36-year tenure, he was instrumental in helping shape Virginia Mason into what it is today, while becoming a nationally acclaimed expert and leader in the health care industry.

In July 1968, he wrote this article, headlined “Looking Ahead,” for the staff newsletter:

“The completion of the West Wing – East Wing development was obviously a significant milestone in the continuing program of modernizing and updating our medical center facilities. Although the dust has settled, and we can turn once again to a more normal course of daily events, we must focus our attention during the several months ahead on several important and, somewhat neglected, programs.

The first of these relates to brushing up on the ‘gracefulness of care’ rendered our patients. The patient who enters our institution looks for more than just sophistication in their care. They expect to be treated as an individual by people who have warmth and understanding and who will do more than the minimum to make them comfortable. It is our firm belief that the employee who has these qualities of warmth and understanding makes a considerable contribution to that patient’s recuperative powers. The attitude of the patient in their surroundings has a bearing on their acceptance of medical advice and treatment.

Virginia Mason Hospital has always had a tradition of caring. During construction and growing periods, some of these fine edges of personal service and personal consideration may become rough. It is our sincere hope that jointly, over the next several months, we can concentrate as a group on rededicating ourselves to improving on some of these finer practices.

What do we mean when we talk of the ‘gracefulness of care?’ Some specific examples:

You become aware, by listening, of the extremely high noise levels in patient care areas – the squeaky casters on the equipment, loud voices, the too frequent use of the page system for individual staff convenience. You watch for the softer touches, for example, how are patients transported through the hospital – with cold dispatch or with friendliness and consideration? Gracefulness has to do with the types of conversations that take place in elevators with patients present and the many other indicators of sensitivity.

The list of do’s and don’ts could be endless, but the point to emphasize is that each of our patients need to be treated as we would expect ourselves treated in a similar situation, and with respect to privacy and medical condition. If problems occur – and they are bound to periodically – then, since the patient is a guest in our home, we should right those wrongs by apology or by special attention.

We would urge your whole-hearted participation in the months ahead to bring additional warmth and caring into our patients’ lives. This is our tradition and, although we may be doing ‘all right,’ I think we can all admit that we could do better.”

John Ryan, MD: Practiced at Virginia Mason Starting in 1978

(Excerpted from an interview by David Wilma on May 30, 2018)

“My father was a surgeon, a urologist. He was associated with Tate Mason, the son of the founder of Virginia Mason, so I was aware of the organization. When I started my surgical residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Virginia Mason was well known there.

In 1977, I wrote a letter saying I was a young guy looking for a job. There were many jobs open in surgery at the time and I interviewed all over, including at the University of Washington and Harborview. Harborview was a trauma hospital and wasn’t really interested in trauma at all. So, I left Harborview and walked down to Virginia Mason. I came in the door and for some reason thought, this is the place. I was impressed that nobody was talking about leaving. Everyone seemed to stay there their whole career and that meant something to me.

The thing that really made it good for me is that I knew it had a good local and national reputation, which was enhanced by the way surgical staff related to residents, called house staff. Each surgeon had two residents dedicated to them around the clock.”

Elizabeth Braun

Virginia Mason

“I have had the delight and honor of both working for Virginia Mason and being a patient since 1988. I have watched the organization add or replace numerous clinics and hospital additions. The buildings are my children. Designing, building and watching them evolve has been tremendously satisfying. The care is what excites me about coming to work every day! I have watched as my family’s lives, and my own life, were literally saved several times because of our outstanding care. I know this comes from our commitment to being the quality leader, and the creativity and devotion of the staff. Thank you all!”

Laura Jeffs

Virginia Mason Seattle

“Founded in 1984 by Virginia Mason’s first psychiatrist, Ted Rynearson, MD, and Jacki Meurk, former board member, the Separation and Loss (Grief Services) department offers individual and group support to sudden, traumatic death (homicide, suicide, accident, overdose and illness) survivors using Dr. Ted Rynearson’s Restorative Retelling model. Dr. Rynearson literally “knocked on doors” at the Department of Justice in Washington, DC, to share about the services to be offered and request grant funding to support the program. Partially funded since 1998 through a DOJ crime victim service grant, the team has expanded services to include: critical incident debriefs within Virginia Mason and in the community; Restorative Retelling Facilitator trainings; regional and national trainings on traumatic death and related topics; and consultation. Several group intervention outcome studies have been published, and Dr. Rynearson won the Association of Death Education and Counseling (ADEC) researcher of the year award in 2013. He has consulted with Israeli and Palestinian clinicians on the model, as well as with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The small team of Laura Takacs, Laura Jeffs and Dr. Ted Rynearson is grateful to Virginia Mason for its ongoing support.”

(left to right) Edward Rynearson, MD, Laura Takacs, LICSW, MPH, and Laura Jeffs

Lauren Lindeman: Facing Cancer with the Team Behind You

(This article was written for Virginia Mason’s Health & Wellness blog in 2015.)

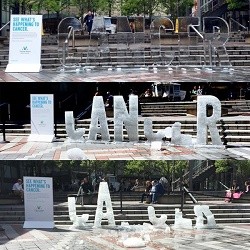

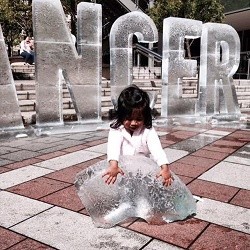

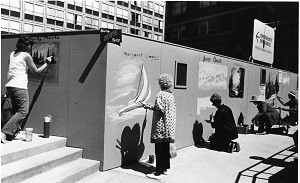

One sunny day in downtown Seattle, Virginia Mason made cancer disappear. Five-foot tall letters made of ice spelled the disease, then slowly broke apart into icy rubble under blue sky at Westlake Park. Part of the ‘See What’s Happening to Cancer’ campaign, Virginia Mason physicians and health care experts were near the sculpture to provide information on cancer prevention and screening.

We asked Virginia Mason team member and breast cancer survivor Lauren Lindeman to talk about how she experienced the event.

How was this event personal to you?

“In January 2015, I was diagnosed with very early stage breast cancer. The early detection made possible by 3D mammography meant I could undergo a lumpectomy, have radiation just once during the surgery, and not need chemotherapy at all. Even though we’ve all heard the words ‘early detection’ like a mantra, it’s finally real for me. It may take some time and persistence, but cancer can be defeated. I loved how the ice sculpture symbolized that in such a tangible and visual way.”

What did it mean to you as a Virginia Mason team member?

“Many members of our leadership team made a special trip down to see and support this amazing concept that cancer can and will be overcome. Throughout the day, team members from all areas and job descriptions used their breaks to come see the sculpture. It gave me a true sense of pride in our Virginia Mason family and reflected the commitment we all feel in our role as patient ambassadors.”

How did it feel to be at the sculpture site?

“Joy and excitement within myself and also from the crowd. Who knew it could be so exciting to watch the letter E disintegrate or see a chunk of a C crash loudly to the ground, or better yet, watch a survivor pose for a picture where she was ‘kicking cancer?’”

What did you see and hear from others?

“Throughout the day, people shared incredible stories of their own battles with cancer. Either they had been touched by cancer personally or experienced it with loved ones. Those who had lost loved ones to cancer were especially supportive of our efforts. Everyone wants to rally together in this fight, and that was truly amazing to see.”

Any particular moments that stood out for you?

“After hearing my story, several women admitted that they were way overdue for a mammogram and committed to get in right away. There was a beautiful little girl who was trying to melt a fallen chunk of the letter C with her tiny hands. An 80-year-old man shared his story of beating prostate cancer and being able to visit his children in Seattle. Then there was the roar of the crowd every time another letter bit the dust.”

Lauren Lindeman

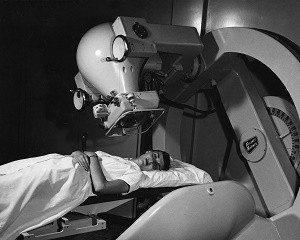

Birth of Nuclear Medicine

(Excerpted from “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

“Soon after World War II ended, the X-ray Department experienced numerous changes. One, which had national importance, was development of the radioisotope. With the announcement of the atomic bomb, it became clear that radioisotopes might soon be available for clinical use. Thomas Carlile, MD, was especially intrigued with the potential clinical use of isotopes and spent the summer of 1947 studying medical applications of nuclear physics at the University of California. Soon after, he introduced radioactive phosphorus and iodine to the hospital early in 1948.

‘At the time, we had to do our own calibration,’ Dr. Carlile later said. ‘We didn’t receive commercially packaged isotopes as we do today. Rather, we received bulk materials from the Department of Energy’s National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It arrived in huge, lead-shielded containers. We would have to take these raw isotopes and refine them for clinical use. At the time, we were supplying the University of Washington and Swedish Hospital’s Tumor Institute on the basis of the calibrations that we did here. I would work night after night with one of our residents calibrating these isotopes and getting them ready for human use.’

Ultimately, the need for standardization of radioactive isotopes on a national scale led to the formation of the Society of Nuclear Medicine, which was born in the Pacific Northwest and then developed chapters across the country. Dr. Carlile was a founder and became the society’s first president in 1953.”

1957: First Cobalt-60 cancer treatment in the Pacific Northwest was offered at Virginia Mason.

First Radiologist at Virginia Mason

(Excerpted from an interview with Thomas Carlile, MD, by William Steenrod Jr., MD, on April 16, 1988)

“There was a time when Virginia Mason was known as the Mason-Blackford-Dwyer Clinic. Dr. Maurice Dwyer was Dr. Mason’s first partner. In 1914, when Dr. Mason came to Seattle, Dr. Dwyer was in general practice.

Dr. Dwyer was a short, frail man who had a bad limp from hip dysplasia. Compared to Dr. Mason, Dr. Dwyer wasn’t a particularly dominant figure, but complemented him well as his right-hand man. When Dr. Blackford came out from Rochester, Minnesota, it became the Mason-Blackford-Dwyer Clinic. When the Dowlings came along, it was decided they couldn’t keep adding the names of every doctor added to the group. I think Dr. Palmer was the last one to be added. It was about that time that they finally dropped everybody’s name, except Dr. Mason.

Dr. Dwyer became interested in X-ray early on and followed its development in the Northwest. He began attending X-ray meetings and spent some time at Mayo and other reputable clinics in Washington, DC. When The Mason Clinic formed its Board of Internal Medicine, Dr. Dwyer was honored as a grandfather of the specialty. By the early 1920s, he was a leading radiologist in Seattle – one of the first two or three.

Dr. Dwyer branched out into X-ray therapy and installed the first X-ray therapy unit at The Mason Clinic. In 1935, he was granted a grandfather certificate in radiology. He held certificates in internal medicine and radiology. Since the internal medicine doctors told him he had to choose between them, Dr. Dwyer kept his radiology certificate.

Unfortunately, he had hypertension and his vision was failing. When Dr. Dwyer died in 1944, we definitely missed him.

The Seattle radiologists were particularly good to me after Dr. Dwyer’s death. They were very generous with their time. Harold Nichols, MD, who was a very prominent radiologist, offered me a job, but I wanted to stay at The Mason Clinic. So, I took my boards in 1945 and, soon after, became a partner. I ran the Department of Radiology by myself for two years for a salary of $500 per month.”

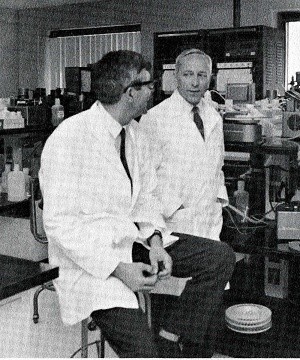

Maurice Dwyer, MD (left) with J. Tate Mason, MD

Virginia Mason Co-founder John Minor Blackford, MD

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

In 1917, Dr. Blackford was practicing medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. when Dr. Mason – who was attending a medical conference at Mayo – met him. The two became fast friends and Dr. Mason then asked Dr. Blackford to join him in practice in Seattle. Dr. Blackford had been active in research in cardiology and diseases of the thyroid gland at the Mayo Clinic and later, high blood pressure and gastroenterology. He participated in the installation at Virginia Mason of the first electrocardiograph machine west of the Mississippi River. He performed clinical research while in practice and presented a number of original articles to medial organizations, especially in the field of gastroenterology. He also encouraged members of the medical staff, especially younger physicians, to become involved in clinical research and present papers whenever possible. Dr. Blackford was a large and friendly man who enjoyed a host of friends, both inside and outside the medical profession. He inspired a confidence in others and developed a large practice involving many community leaders. He enjoyed the respect of his medical colleagues and was often called in consultation for medical problems. He was a genius at analyzing the problems of patients and always added something to the diagnosis. Dr. Blackford was a husband, father of three as well as an ardent bridge player and yachtsman. He was very proud of his yacht that bore the name of his youngest daughter, Sally Bruce. He was an inveterate smoker of cigarettes and always kept a tin of fifty cigarettes in his pocket. He had a particular type of cigarette cough which, at times, was severe enough to render him temporarily to lose consciousness. His peers felt that his cigarette smoking probably contributed to his death from pneumonia.

John M. Blackford, MD

Eileen Dunning

Virginia Mason Seattle

“As a proud Virginia Mason retiree, I’ve recommended the health system to a number of people, including three family members, friends and several people from my church. Sometimes it’s been a matter of helping them find a provider who I view as exceptional and other times it’s been something that required more immediate attention. Regardless, Virginia Mason has never disappointed.

A person very close to me had a myocardial infarction and was deciding between having it stented versus bypass surgery. Although she had been a longtime patient of another Seattle-based health system, I persuaded her to obtain a second opinion from Virginia Mason interventional cardiologist Wayne Hwang, MD. Dr. Hwang discovered a blocked carotid artery, which had gone overlooked where my friend had previously been seen. She decided to have carotid artery and coronary artery bypass surgeries at Virginia Mason. My friend, her family and I were so pleased with the medical and nursing care she received. A few years later, my friend developed unrelated, acute complications and died in the Critical Care Unit at Virginia Mason. Her care could not have been better and was provided with incredible compassion and respect for her family.

I am always incredibly proud to recommend Virginia Mason to people I care about. I respect the expertise that I know the health system seeks and maintains among their providers. I also respect the expertise of the nurses and other professionals caring for patients.”

Sandy Novak: Virginia Mason Administrator Starting in 1978

(Excerpted from an interview with David Wilma on Jan. 7, 2019)

“When I was working in human resources (HR) The Westin Seattle, I heard that the director of HR at The Mason Clinic had accepted a job at Boeing. A colleague thought it would be a good opportunity. So, I contacted Austin Ross and met Bob Boyle, senior assistant administrator, at Trader Vic’s restaurant because I wanted to impress him. In June 1978, Austin hired me as HR director for everyone but physicians. That was out of the chairman’s office.

“After a few years in HR, I decided I wanted to be in a broader operation role. When I arrived at Virginia Mason, there were no female physicians. Even me being in an administrative role was pretty innovative at the time. So, I was always aware that I had to be better than the best. I was very driven to make sure I was making a positive impression. I felt like I had a lot of responsibility being one of the few women there. A few years later, Dr. Detweiler was hired as a pathologist with no thought that she would be a partner.

“Later on, a new assistant administrator position opened at the clinic. However, an administrative fellow was being groomed for the position. Despite feeling like I didn’t have much of a chance, I spoke with Austin Ross and told him I’d like to throw my hat in the ring. Being the reasonable administrator that he was, Austin said OK. Thankfully, unbeknownst to me, I had strong support from a number of physician leaders. The compromise was that we would have two positions and I would have one. After a year, the fellow would find something else.

“I really liked working for Austin. One of the smartest decisions he ever made was assigning one administrator to support each section. Every section head knew who their go-to person was. In some ways, this was more work for administration. But it helped develop closer ties between physicians and leadership. There was more of a collegial feeling than I saw in other organizations.

“Austin Ross was a masterful strategist who thought about the physician colleagues and how administrators should interact with them. That’s what his style was.”

Sandy Novak with Austin Ross

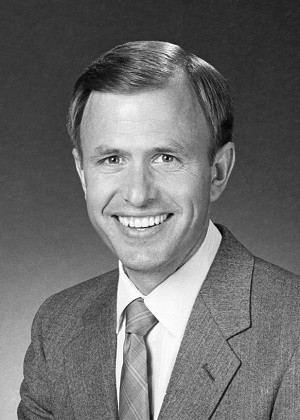

Roger C. Lindeman, MD: Practiced at Virginia Mason Starting in 1968

(Excerpted from a 2005 monograph by Dr. Lindeman and an interview in 1998)

“It was 1967, during my first year at Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania as a captain in the Army, that I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Phil Jolly. He was applying for a position in the Department of Surgery at The Mason Clinic in Seattle. The Chief of Surgery from The Mason Clinic was coming to Valley Forge to watch him operate. I remember being impressed that The Mason Clinic was that careful in deciding whom to hire. Dr. Joel Baker observed closely as Dr. Jolly did two rather complicated cases. Needless to say, Dr. Jolly passed with flying colors and his future with The Mason Clinic was assured.

I had the opportunity to meet Dr. Baker and learn more about The Mason Clinic. He mentioned they were looking for a specialist in otology and neurotology, as their current otologist was about to retire. Shortly thereafter, I received an invitation from Dr. Baker, asking my wife, Lillian, and I to come to Seattle for a two- or three-day visit.

This was an impressive visit. I was presented with a full schedule of half-hour appointments with physicians in almost all specialties. There were visits and tours arranged for Lillian, as well. The final appointment for me was with Dr. John Walker, chairman of the clinic. I was surprised that he already knew so much about me. I will always remember Dr. Walker’s comments as he was describing the uniqueness of The Mason Clinic.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘our physicians have the opportunity to practice very high-quality health care in a setting of medical education and research. Most of us are very active in both clinical and academic endeavors. I think you would find in each section, and in each specialty, one or more physicians who know as much about their specialty as anyone in the country!’

Lillian liked Seattle and especially the people she had met. I couldn’t help but think what a privilege it would be to be able to teach, participate in clinical research and practice with outstanding physicians of like mind and common purpose. Before leaving, I met with Dr. Walker again. He made an offer and I accepted.

In March 1968, I was discharged from the Army and drove cross country to Seattle to join The Mason Clinic’s Otolaryngology section. Lillian and our three kids joined me soon after. My clinical practice grew rapidly and I enjoyed teaching otolaryngology residents at the University of Washington. Soon, we established an official rotation for UW residents at Virginia Mason Hospital.

Through the generosity of Mr. William G. Reed, we established the Reed Laboratory for Research in Otolaryngology. Our most significant contribution was probably a new surgical procedure called the tracheal diversion procedure. This is a reversible procedure designed to protect the lungs from aspiration pneumonia in patients who, at least temporarily, were experiencing laryngeal paralysis as a result of a brain tumor, stroke or other neurological disorder. I wrote the article describing this procedure, which soon became known as the Lindeman Procedure.

My practice continued to grow, mainly in otology and neurotology. We became a referral source for patients with acoustic tumors.

I could not have accomplished this work without the complete cooperation of Dr. John Tytus, section head of Neurosurgery at The Mason Clinic. Acoustic tumor surgery had long been considered within the domain of neurosurgeons. Many resisted this ‘invasion’ by neurotologists and refused to cooperate. This was partially true in Seattle, but not at The Mason Clinic. What an advantage it was to work as a team in a group practice setting. Neurosurgeons, locally and nationwide, eventually agreed to cooperate. But by that time, we had established a solid reputation and attracted patients from around the Pacific Northwest.

I think I was the 55th partner, so I would have been The Mason Clinic’s 55th doctor. We practiced just specialty care. We didn’t practice primary care until 1975. We were all located on one campus near downtown Seattle. We didn’t have any satellite clinics at the time. There was a wonderful esprit de corps, a wonderful collegiality that was present. The older doctors would say, ‘Well, it just isn’t like it used to be when we had nine partners and could have partners’ meetings in someone’s home.’

The people make it a great place to work. We have always tried to attract the very best physicians, nurses and administrators.

In February 1980, I was elected by the physician partners to be chairman of The Mason Clinic for a four-year term. There was a lot to learn despite my previous experience and participation in management courses. At The Mason Clinic, the physician chairman works closely with the clinic’s executive administrator. It was my good fortune to team up with Austin Ross, who was serving in that capacity. Austin was not only a highly skilled administrator, but a professor of health care administration at the University of Washington. What more could a new chairman ask for? It was a pleasure to work with Austin until his retirement in 1991.

I was reelected by the partnership for four additional four-year terms and served as chairman of The Mason Clinic – and later chairman and CEO of the medical center – from 1980 until my retirement in 2000.”

John Knab

Virginia Mason Seattle

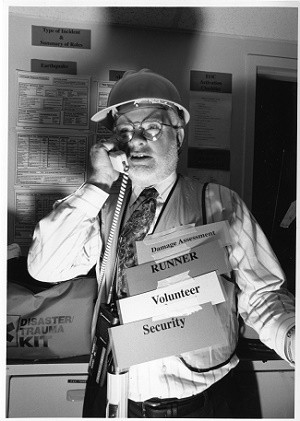

“I remember being in the operating room one evening as a third or fourth year Virginia Mason anesthesia resident in 1996 or 1997. As I looked at the anesthesia machine, it began to wobble and shake, and I thought maybe I was inhaling too much sevoflurane. Then, as things began to shake throughout the room, including my colleagues and the patient, I realized that we were in the middle of an earthquake. My first and only!”

First Baby Born at Virginia Mason Franciscan Health Birth Center

“I had the privilege of being the first woman to give birth in the new Virginia Mason Franciscan Health Birth Center. In April 2020, while COVID-19 was turning the world upside down, I suddenly and unexpectedly became a single mother to my two young children, with No. 3 on the way. In my grief, Virginia Mason team members were a rock of stability and staff from Franciscan Women’s Health at Virginia Mason offered me their unwavering support, grace and strength through one of the darkest periods in my life. On the morning of Aug. 11, 2020, I arrived at the Birth Center tired and very ‘over it.’ Although I knew in advance it was a possibility and that staff knew I was coming, I was still surprised to learn I was first! There was a giddy, nervous energy in the air. Everyone was excited! My nurses respected my boundaries through the labor, offering me the encouragement I needed, while allowing me the space to labor on my own. Despite a valiant effort from the Anesthesia team to get me an epidural once the time came, the baby and my body had other plans. I transitioned quickly and, as the team brainstormed how to manage my unrelenting pain, I realized I would soon meet my newest child. A sea of familiar faces surrounded my bed, and at 5:45 p.m., my obstetrician safely delivered him and I lifted my son to my chest. Zachary entered this world surrounded by love. When I checked my phone several hours later, a slew of text messages from my peers revealed that the whole hospital knew he had arrived – a little light in a time of seemingly unrelenting darkness. I will forever be grateful for all the nurses and doctors who held my hand – literally and figuratively – through my pregnancy, birth and postpartum care. It was a huge relief to confidently place my trust, and my child’s health, in the hands of a competent and compassionate team. Thank you!” – Natalie Dively, NA-C, Critical Care, Virginia Mason Medical Center

Harold Dill

Virginia Mason Seattle

“My first introduction to Virginia Mason was in early 1959. I had just come out of military service and was hired by Northern Commercial Co., which had numerous stores in remote locations of Alaska. Each of their managers being sent north had to pass a physical examination administered by Virginia Mason. In subsequent years, it became an annual event as we all returned to Seattle for our managers meetings. My physician was Dr. Randolph Pillow. I will never forget him. I was so impressed with his patient skills and medical knowledge. He was my hero for many, many years.”

James Tate Mason Jr., MD: Virginia Mason Physician, Son of Founder

(Excerpted from a video interview in 1988)

“My professional life with my father was very limited. He died when I was 22 and in my first year of medical school. When I was a boy, I made many visits to the hospital. When I was six or seven, I went while the hospital was being built. My mom and dad were looking at what was going on. They looked up aghast at me four stories up in the scaffolding. That resulted in my first spanking.

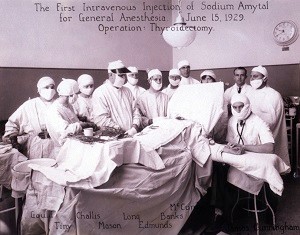

“I remember my dad operating and teaching all the time. There were always visitors from all over the world. He had a visitors book in surgery that he was proud of … people who came through signed their name and where they were from. At the time, Seattle – along with the Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic – were known for thyroid. Dad made his name in thyroid surgery.

“My dad was so honest that in 1920 he wrote an article for the Journal of the American Medical Association on mistakes in 100 thyroidectomies. Think about how many doctors have written about their mistakes. He loved people. He loved to talk. He was unflappable. Something would go wrong in surgery and it didn’t bother him a bit. He’d stop surgery, turn around, wash his hands and tell a story. Then he’d come back and finish the case. He was never curt. If a resident did something wrong, he’d never call them out. He’d simply explain why it should be done another way.

“Dad was not a businessman or administrator. Had it not been for Mr. Dare Sr., I’m convinced the hospital would not be where it is today. Mr. Dare was known as the ‘no man.’ The doctors always wanted to get their money. He would say, ‘No. Not until the bills are paid.’

“At the end of their first year of business, the partners were $40,000 in the red. They didn’t have a dime. The president of Seattle Bank was Mr. Kelleher. Mrs. Kelleher happened to be my godmother. Dad went to Mr. Kelleher and said, ‘We need $40,000. You’re my son’s godfather. You’re from Virginia and so am I.’ Mr. Kelleher said, ‘I’ll loan you the money, but the partners’ wives need to sign the agreement so they know how in debt you are.’ I never saw my mom madder. But she went down and signed, along with the other wives.

“My dad’s biggest disappointment was that he never taught medical school. When he was ill in the hospital, he said, ‘I know I’ll never be able to operate again, but I’m going back to the University of Virginia to be a professor of surgery.’”

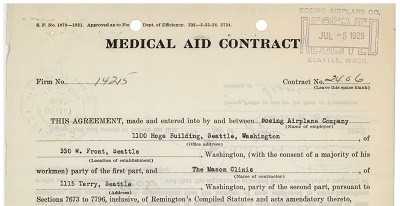

John Dare: Mason Clinic, Hospital Administrator Beginning in 1935

(Excerpted from interview by Dr. William Steenrod on Oct. 11, 1985)

“Talking about the Depression. We used to have plenty of credit problems. Patients had a terrible time paying their bills. Those were the early days of neoarsphenamine that they used to treat syphilis with. We had a rule in the clinic that you couldn’t get that treatment without paying cash in advance. It probably preserves the moral character of the individual, although it wasn’t all that good.

The physician partners had just bought an X-ray deep therapy machine. They had the only one in town for the early treatment of cancer. It cost them a lot of money. They were so wounded financially by buying this gadget, that they made patients pay for their deep therapy treatments in advance. Of course, you could come into the clinic and get any other treatment in the world on credit, but they marked out these couple of things as they needed money in advance. The Depression went on a lot longer than we all thought it might. Everything seemed unchanged up to about 1939.

The physician partners ran the clinic on a nightshift for quite a while. They were the principal doctors for Boeing in the early days, when they had an ambulance and nurse down there. We used to examine all their new hires and, in 1939 – when they started hiring by the hundreds rather than just a few – we had a heck of a problem trying to take care of them all.

We were getting five or six bucks an examination, including the lab work. They were coming in mounting numbers. So, the clinic started staying open nights in 1940 or 1941. They put on a nightshift and the physician partners would alternate coming in every third night. During the course of an evening, they would go through a couple hundred Boeing exams, do all the lab work and clear them for employment with Boeing. Although it might have killed off a few of the docs, this very unusual work was damn good financially.

Everybody took their turn. Dr. Blackford and his physician partners came down and worked nights. The sad part was that World War II was starting. Income tax started moving up fast and they probably took all the night work and gave it to the Government anyway. Boeing eventually hired its own medical staff. They had to. We got rid of the challenge.”

1929 clinic contract with Boeing Airplane Company

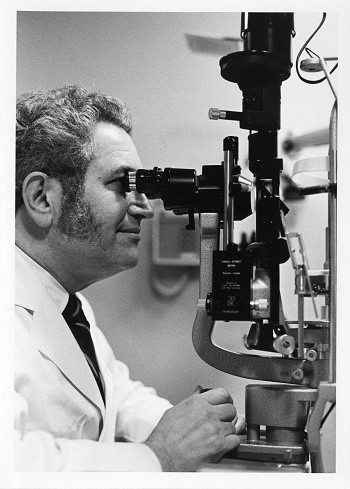

Melvin Freeman, MD: Ophthalmologist Who Started at Virginia Mason in 1979

(Excerpted from an interview on Nov. 3, 2016)

“Because my father was an optometrist, I wanted to go into the health care field. My folks told me I could go to any medical school I wanted, as long as it was the University of Washington and I lived at home. So, taking that advice, I decided to go to UW and reside at home. We lived in Montlake. So, that was an easy walk to the university. At that time, tuition was $75 per quarter, but the medical school was much more expensive. It was $150 a quarter. So, that’s why I lived at home.

In those days, you could get into medical school after three years of college, and you did not have to pick your residency until your internship year. I graduated in 1960. You had an internship, general internship and then – during that year of your internship – you actually applied for your residencies. Because of our family interest in eye care, it seemed to me that it was such a small organ I really should be able to master it. Little did I know that wasn’t true. I applied and got a very nice residency at Washington University Barnes Hospital. I was out of town for 10 years.

My first experience with Virginia Mason was in the 1950s when I was diagnosed with a heart murmur and my family doctor sent me to see Robert King, MD – a specialist in the old hospital building. I still have the note Dr. King sent my family practitioner with all the names of who were the internists at Virginia Mason, which was a very short list of four or five. Turns out, I may have had rheumatic fever as a child, but I had no limitations on my activities.

I later joined Virginia Mason in 1979. I was in Boston doing my fellowship and became interested in returning to Seattle. There were three opportunities: University, Group Health and Virginia Mason. I was out in August and had interviews with Drs. Joel Baker, John Walker, Pearson and Randy Pillow. I went over to Dr. Walker’s house for a dinner, got the flu, fainted and they revived me. I thought for sure that was the end of my career at Virginia Mason. But, no, they came in with an offer. Apparently, they must have done a complete physical on me at that time and felt I was healthy enough to work here. So, I was offered the opportunity to come here, and it was very exciting because I had two other offers.”

Why build a hospital?

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

In part, the Mason-Blackford-Dwyer Clinic group’s urgency to build a hospital was fueled by the great influenza epidemic of 1918-1919 (the “Spanish flu” pandemic), which demonstrated a serious shortage of hospital beds in Seattle. But the underlying reason was that Dr. Mason and his colleagues wanted to have the freedom to develop a new style of medicine patterned after the fast-growing Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. What they planned was a combination of a privately owned hospital and a group practice of specialty trained physicians – a medical center of a scope and quality available nowhere else in the West. Group practice was frowned upon by traditional physicians of the time. In those days, it was only acceptable for physicians to be in solo practice.

The hospital they envisioned would house modern laboratory and X-ray facilities, surgery and delivery rooms as well as sufficient space for 80 inpatient beds. The main floor would have private offices for clinic doctors. The whole organization would be operated under joint management of the clinic and hospital.

Months before, in discussions with his friend, Dan Kelleher, president of the Seattle National Bank (later Seafirst and now Bank of America), Dr. Mason had revealed his idea of the combined hospital and clinic facility. Kelleher replied, “Go ahead, Tate. I will see you through,” which was a statement that would prove to be prophetic.

The dream began to take form from there. Plans were developed in 1919 and the hospital site was chosen. A corporation was formed and bonds were purchased by clinic doctors and others, which provided money to begin construction.

Anonymous

Virginia Mason Seattle

“In October 2015, I was admitted into the Emergency Department with a .39 BAL (bioartificial liver). A severe, late-stage alcoholic at the age of 36. In full restraints (which was necessary after an attempt to run), one of the patient care technicians (PCT) was assigned to sit watch at my door. During my stay, she talked to me, not at me. She didn’t judge me. She got to know me as a person, not an addict. Turns out she was the mother of one of my son’s friends, who had spent many after-school hours in my home. She volunteered to work a double shift so she could stay with me. She arranged for my friend, who was a new mom and nursing, to have access to a breast pump. When my friend realized she had taken the car keys with her, leaving her husband stranded without car seats for three kids, my PCT drove to my friend’s house and dropped off the keys at the end of her shift. The kindness, compassion and understanding she gave has stayed with me. She is a part of my journey into a life of recovery where, in October 2019, I will celebrate four years clean and sober. When I was at my jumping-off point, as low as I could get, she showed me grace and compassion.”

Melissa Jackson Witek

Virginia Mason Bainbridge Island, Virginia Mason Kirkland and Virginia Mason Seattle

“Late at night and with our 10-month-old daughter in tow, my husband rushed me to the Virginia Mason Emergency Department on First Hill in Seattle. I had just been told by my optometrist at Virginia Mason Kirkland, who I had seen for a retinal hemorrhage, that my blood work indicated I had leukemia. I was in acute distress and had serious symptoms related to an extremely elevated white blood count. Sometimes the best things happen at the worst of times. Dr. David Aboulafia happened to be the oncologist on call that night. That was almost 20 years ago. With kindness, a gentle bedside manner, and a medical knowledge beyond compare, Dr. Aboulafia has seen me through a bone marrow transplant, several serious post-transplant infections and complications, five joint replacements, several eye surgeries, and the long-term side effects of my treatment. He has coordinated my care with other Virginia Mason departments, as well as with the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, where I had my transplant. I remember a nurse in the Emergency Department that night telling me that my baby girl was my reason to live. Because of Dr. Aboulafia and great care from the entire team at Virginia Mason, I am excited to celebrate my daughter’s 21st birthday with her later this year!”

Medical Advances Involving Large Mammals

(Excerpted from “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

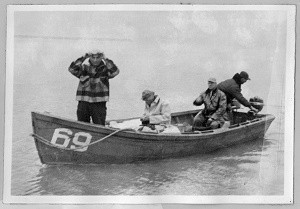

“In 1934, Virginia Mason’s Bob King, MD, teamed up with Paul Dudley White, MD – a physician from Harvard and President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s cardiologist – to perform the autopsy on ‘Tusko,’ an elephant at Woodland Park Zoo.

“Years later, the two research partners joined up again in the Bering Sea, where they conducted the first cardiogram on a whale.”

1952 “Whaling expedition” including Drs. Robert King and Paul Dudley White.

Robert Mendoza, PCT: Good Care Begins with Trust

(This team member profile article was originally written for posting on Virginia Mason’s intranet, V-Net, in April 2015.)

Listing the duties of a Patient Care Technician (PCT) would fill a notebook, and yet no regular job description would capture what Robert Mendoza, PCT, brings to his patients. There is assisting with treatments, medications, checking vital signs, help with transferring, personal care, and ongoing documentation, just for starters. But for Mendoza, there’s something else needed in the mix: a patient’s trust.

“I like to build trust with my patients through communication,” said Mendoza. “Connecting with them in conversation or with laughter helps patients feel comfortable with me and what I’m doing.”

Mendoza knows that trust also comes from a patient’s confidence that help will be there when they need it. He visits his patients regularly without waiting for the call light, asking if there’s anything he can do. Mendoza can tell when a patient is distracted, sometimes by pain or anxiety, and might not be aware of their own needs. That is when he will suggest something – a different position or a warm shower, perhaps – that could help them feel better.

“Sometimes what they need is for someone to listen,” said Mendoza. “There’s no medication that can help with that. So, I stay and talk with them.”

Since even routine patient care, like getting vital signs, can feel invasive, he makes sure to describe step-by-step what’s happening. It is one way to show respect for his patients, as he tries to put himself in their place. Having empathy for his patients comes naturally to Mendoza, which he attributes to loving what he does. One of the biggest rewards he says is seeing people get better.

“I give my patients quality care and a good patient experience because I work from my heart,” said Mendoza.

Robert Mendoza, PCT

Jerry Sluman: Grateful Kidney Transplant Recipient

“After steadily watching my kidney function decline over the course of seven years, I was informed that I was ‘running out of runway.’ My kidneys had officially failed. It was time to swallow my pride, share my story and search for a living donor. After persistent campaigning, I was lucky enough to have 30 people go through the donor screening process. Of those 30, three were potential candidates. Of those three, there was one exceptionally matched friend. His name is Brock Sabo and he was generous enough to donate a kidney to me. Our surgeries took place at Virginia Mason Hospital Aug. 7, 2018.

“Everyone at Virginia Mason took outstanding care of both Brock and I. This includes Nephrology, surgeons, nurses, therapists, dieticians, social workers and every other team member who took part in our successful care.

“I couldn’t imagine receiving better care across the board and am extremely grateful.

“A special thank you to all the special, empathetic people who helped me through the process to achieve a second lease on life – especially Virginia Mason team members, Brock and Sarah Sabo, Jodi and Patti Baker, Kristin Henderson and Ryan Aal!

“Happy 100th birthday, Virginia Mason. Keep up the great work!”

Kidney transplant recipient Jerry Sluman (left) with his friend and living donor, Brock Sabo (right).

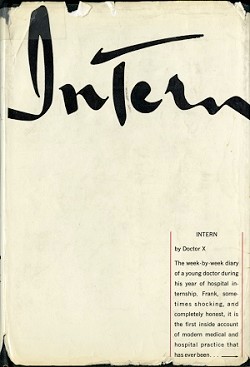

Best-Selling Book in the ‘60s Described Experience of a Virginia Mason Intern

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”; Written by Charles Hammer, MD)

“In July 1960, Alan Nourse, MD, who had been an intern at Virginia Mason in 1955, published his book, ‘The Intern,’ under a pseudonym (Dr. X). This national best-seller was a thinly disguised account of his experiences as a housestaff officer at Virginia Mason Hospital.

“Dr. Nourse assigned pseudonyms to many of the active partners in the Mason Clinic, but his descriptions of the characters were so accurate that we could easily tell who was who.

“At times, the person portrayed would deny that he was the character in the book (especially if the description was not particularly complimentary), but the rest of us knew who was who.

“In truth, the most disappointed partners were those who could not find their resemblance in print.”

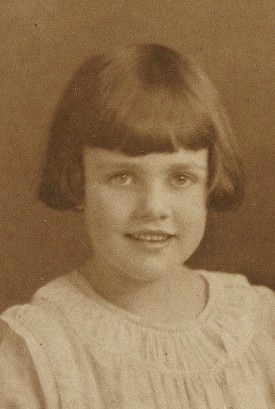

“The real story of how the hospital was named,” according to Virginia Mason Blackford Morris

Miss Virginia Mason raised Virginia Blackford’s grandmother, because her grandmother’s mother had died; Miss Virginia Mason was her grandmother’s aunt.

When John Blackford was born, it was not considered proper for “the boys” to potentially “hear something” related to a woman in labor. So his mother was put in a carriage and driven 2 miles down the road to Miss Virginia Mason’s house, and that’s where he was born.

Later he roomed with her while at the University of Virginia; she ran a boarding house for medical students. So, as his great aunt, surrogate grandmother, she had a great bearing on his life, and his mother’s life, which is why he named his daughter after her, Virginia Mason Blackford.

When the two mothers, Mrs. Tate Mason and Mrs. John Blackford, were together one evening while the doctors were down polishing the floors before the hospital opened, they were discussing what a coincidence it was that there were two girls with the same name. (The other Virginia Mason was supposedly named after the state of Virginia.) So the two mothers decided this would be the perfect name for the hospital.

Recorded Sept. 25, 1996 with the Virginia Mason Historical Society.

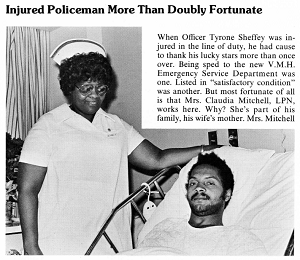

Injured Policeman More than Doubly Fortunate

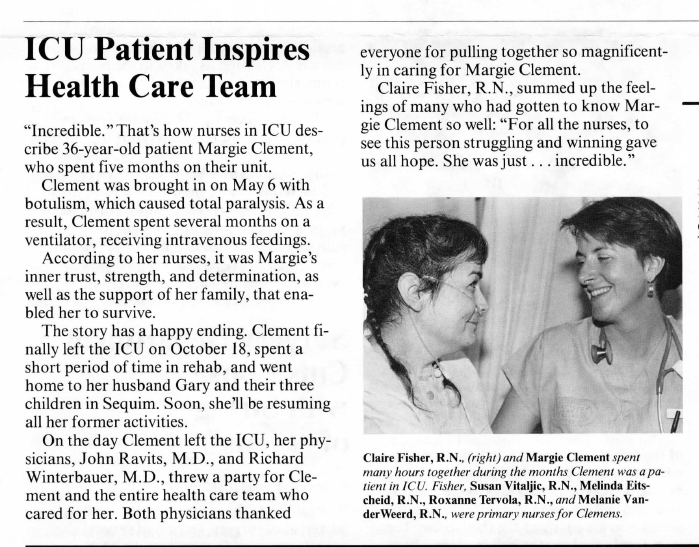

(This article was originally written for the October-November 1975 issue of Pulse, Virginia Mason’s employee newsletter.)

When Officer Tyrone Sheffey was injured in the line of duty, he had cause to thank his lucky stars, more than once over.

Being sped to the new Virginia Mason Hospital Emergency Service Department was one. Listed in satisfactory condition was another. But most fortunate of all is that Mrs. Claudia Mitchell, LPN, works here. Why? She is part of his family, his wife’s mother. Mrs. Mitchell stayed with Officer Sheffey the night he spent in Special Care and was close at hand throughout the remainder of his stay.

Sept. 7, 1975, was a day Mrs. Mitchell, a Virginia Mason Hospital employee of 14 years, vividly recalls: “My daughter called after a couple of police officers came to her house. She said she was bringing the children over because something had happened to her husband. After she hung up, I immediately called the Emergency Room, and they told me his condition was satisfactory. After we arrived at the Emergency Room, we saw he was in pretty good spirits. But we were just numb.”

“They let me stay with him all night in Special Care. He said later that he knew I was there and held his hand while he slept.”

Officer Sheffey is home and doing fine now. He does, however, have one problem of serious proportion, responding to the many friends and fellow officers from all over the state who deluged him with cards, flowers and get-well-soon messages.

Mrs. Claudia Mitchell, LPN, with injured Officer Tyrone Sheffey. Mrs. Mitchell is also Officer Sheffey's mother-in-law.

Robert King, MD: Began Practicing at The Mason Clinic in 1931

(Excerpted from an interview by William Steenrod, MD, on April 11, 1985)

“Dr. John Blackford, brother of Stage Blackford, who was instructor in internal medicine at the University of Virginia, encouraged me to come out to Seattle. I went to Clifton Springs Sanatorium and was offered a job there for $3,500 a year. But due to my father's persuasion, I came out here because he thought going to New York was like going to the land of the living dead and, out here, there was considerable opportunity.

I had an uncle who had spent time in Alaska managing a gold dredge in Nome on the Snake River. In the winter, he would spend time in Seattle. He knew Seattle well and was a patient at Virginia Mason Hospital. He also encouraged me to come to Seattle. I was in correspondence with Dr. Blackford and then Drs. Joel Baker and Louis Edmunds wrote to me. I finally came out. I became a staff physician at The Mason Clinic in June 1931.

We were paid $250 a month. We furnished our own car, made house calls and worked in the office. At the end of 1932, I was still making $250 a month. Thankfully, I received a raise to $300, but then my pay was lowered by 20 percent to $240 per month.

We used to borrow $10 from one another to get through the month. Dr. Edmunds was married at the time and was having a little harder time than we were. I went to live with Dr. Baker in a bachelor establishment here in Seattle, called the Hacienda. Drs. Baker, Wilkinson, Edmunds and I took turns making house calls.

Dr. Blackford was the reason I came to Seattle. He took me under his wing professionally and socially. I used to have Sunday dinner at his home almost every Sunday. He and his wife were extremely nice to me. I felt very close to him. He was almost a genius from the standpoint of sizing up a situation. He had a strong feeling for patients’ emotional disturbances. Sometimes, he would spend two to three hours with a single patient, while keeping everyone else waiting. He smoked like a chimney – about 50 to 60 cigarettes a day. He used to carry packs of 50 in his pockets. He was also a boat lover. He spent a lot of time on his boat. However, he gradually developed emphysema and a cough. Sometimes, he would start coughing so hard that he would produce superior vena caval obstruction, resulting in a spasm.”

Robert King, MD

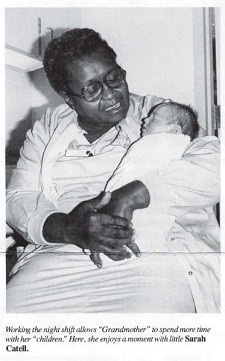

A Notable Nurse: Louella Jackson, LPN

Louella Jackson, LPN, retired from Virginia Mason in February 1989. She was known to staff and patients as “Grandmother” and had the practice of calling babies in the nursery her children. She worked at Virginia Mason from 1966 to 1989.

Don Olson: Virginia Mason Administrator Starting in 1965

(Excerpted from “VMMC History – Reflections by Don Olson,” and an interview by David Wilma on June 1, 2018)

“When I was working for M.D. Anderson and Tumor Institute in Houston, I heard John Dare of Virginia Mason Hospital and The Mason Clinic was looking for an assistant. I had been to the Seattle World’s Fair and decided that if I ever got the chance to live in Seattle, I would grab it. I called John Dare and introduced myself. After interviewing with him, he gave me the job as assistant administrator of The Mason Clinic. We arrived in Seattle on July 12, 1965 and I retired in 1998.

“My arrival at the Virginia Mason Hospital and Mason Clinic found three separate organizations all closely linked. The Mason Clinic was a partnership and the hospital and research center were nonprofits. The heart and soul of the hospital was The Mason Clinic. There were 55 physicians, including the partners and soon-to-be partners. It’s hard to imagine, but for the annual Christmas gathering, we all had dinner at one long table inside Broadmoor Country Club.

“There were no computers to support patient billing. So, we had thousands of pieces of paper that came from physician offices, laboratory, radiology and any other point of patient care service. This paper jungle nightmare was represented in buckets of ledger cards that reflected each patient’s account. Soon after my arrival, we began the process of converting to the IBM punch cards.

“Virginia Mason was a family. Everything operated from the ground up. Patients were the focus and team members who were closest to the patient were the hierarchy. What we excelled in was exquisite patient care. There isn’t anything that goes on in the hospital that nurses don’t know about. If you want to run a good hospital, you’ve got to speak with nurses.

“I never had a bad day there and never had a day go like I thought it was going to go. I was surrounded by very gifted people. We were all pulling on the same rope. Wherever you went around the state, you would bump into people and they would say, ‘You work at Virginia Mason? Oh, my goodness.’ Then, they would tell you their story about how well they were cared for at Virginia Mason. In my era, there we were going into a new age of sophistication, but Virginia Mason had the cards.”

Thomas Green, MD, Orthopedic Specialist

(Extracted from an interview on Oct. 20, 2016)

“I started practicing at The Mason Clinic in 1975. There have been a lot of changes in imaging that have made a big difference in medicine. The most significant one was probably digital X-ray. Obviously, CT scans and MR technology have revolutionized the way we see things. Our ability to quickly move images – as well as view and refine them on a digital framework – was a big improvement that came when we moved into Lindeman Pavilion. Arthroscopy was also a huge change. That was sort of the beginning of outpatient surgery, where you could do significant procedures and people would return home the same day. When I came to Virginia Mason, arthroscopy cases were not being done. So, I started doing them myself. I didn’t have a fellowship or special training, just what I learned from my professors at the University of Washington Medical School.

As a result, I was involved in buying our first arthroscopes for the operating rooms. Don Verg, who was an administrator in Acquisitions, asked me, ‘Do you think this will ever be used enough to justify it?’ I looked at him and laughed. Today, endoscopes are likely the most universally used pieces of equipment in operating rooms, other than maybe pickups and scalpels. Now, my general surgeon colleagues use endoscopes and arthroscopes all the time. The first arthroscopes were modified cystoscopes. They just used a different mechanism to shorten the piece inside.

One of the things I particularly liked in my years at Virginia Mason, was the way the clinic helped facilitate physicians’ care of patients. It was very helpful and appreciated.

If you had a challenge and were not sure what to do, there were always people around to help resolve issues and get things back on track, so patients were taken care of properly.”

Peggy Nystrom

Virginia Mason Seattle

“I was born at Virginia Mason in 1945 and both of my children were also born there. The first on April 27, 1966 and the second on Oct. 24, 1969. The same doctor who delivered me, Dr. Rutherford, also delivered my two sons.”

Jessica Entz

Virginia Mason Bellevue, Virginia Mason Federal Way and Virginia Mason Seattle

“I have been coming to Virginia Mason for more than a decade. I am honored to say that it is my home away from home. I have had multiple sclerosis since I was in eighth grade. Dr. Kita and her staff are like family to me. I trust them with my life. Her knowledge and commitment to me – as a patient, granddaughter, daughter, sister, niece, cousin and friend to many – means so much!”

Virginia Mason’s Development of Satellite Clinics

(Excerpted from the book, “Vision and Vigilance: The First 75 Years, Virginia Mason Medical Center, 1920-1995”)

“As part of a medical staff retreat at Alderbrook Inn on Hood Canal in February 1980, a special report from an ad hoc committee focused the group’s attention on what was to be a major strategy change for the clinic. The decision was made to experiment in the primary care satellite field. The first tenuous move came with the development of affiliation agreements with clinics in West Seattle and Friday Harbor. The medical center entered the field more seriously through the acquisition of Dr. Wes McElroy’s practice at his clinic on Highway 99 near Sea-Tac Airport, where Dr. Ed Meyer served as the first clinic physician to practice away from the main campus. The arrangement lasted for only a short time.

“On Sept. 8, 1980, in a memo to Bob Webb, MD, chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee on Satellite Clinic Development, Dr. Bill Steenrod noted, ‘It seems to me that the only reason to go into the satellite business is eventually to develop into an HMO or whatever the catch phrase is at the time.’ He went on to say, ‘What we are trying to determine at present with the first satellite is whether or not this first step and subsequent ones are bound to land on banana peels.’

“But satellite clinics were in the future. The decision was made to move forward in the summer of 1980and land was acquired adjacent to Evergreen in Kirkland for a new clinic to be called Mason Clinic East. As competition in health care became an accepted fact and routine occurrence, clinic operations were subsequently established in North Bend, Mountlake Terrace, Alderwood Mall, Issaquah, Redmond, Bellevue and Federal Way.

“Much was learned during those years about how to manage separate clinics. One lesson was that systems designed for a large downtown facility did not necessarily work at a branch clinic. Adjustments had to be made. Physicians who practiced in branch sites and their downtown colleagues had to learn how to relate to one another. Bob Webb, MD, was the first clinic physician to operate out of Mason Clinic East and he was joined by Gary S. Kaplan, MD, in 1983. Gary had completed his residency in internal medicine at Virginia Mason, knew the medical center well, and had a great enthusiasm for the development of satellite clinics. He later headed up the entire clinic satellite system.”

Louis Edmunds, MD: Started Practicing Medicine at Virginia Mason in 1928

(Extracted from an interview on April 16, 1985)

“I graduated from the University of Virginia in 1928 and was looking for a job. UV offered me an internship, but they only offered room and board with no salary of any kind. I needed something besides room and board. I finally received an offer from Virginia Mason with room and board plus $50 a month. That offer made the decision for me. I was also given expenses for the trip out and back. So, I travelled to, and arrived in, Seattle on July 1, 1928.

Dr. Bob King also came out to be interviewed and look over The Mason Clinic and he has been here ever since. Then, my sister came out to visit me, met Bob and they now have 17 grandchildren and counting.”

[Margaret Edmunds, Louis’ wife: “I’d like to add something to Louis’ story. They may have given $50 a month to the interns. But, some way or other in the first week – with all their card games – the $50 moved around. When things were really bad, they sold their tickets back home. They were stuck.”]

“We did a lot of State Industrial insurance work and what we called ‘steamship cases’ that came under the longshoreman’s workman’s compensation. Mason Clinic did get into a little trouble with the King County Medical Society. Dr. Mason was quite a go-getter, you might say, in getting business. He signed a contract with the police department to furnish medical care to officers. I forget how many policemen we had then, but there were quite a few. They had contracts with the steamship companies, The Boeing Company and the Postal Service. Because of this so-called ‘contract medicine,’ the Medical Society stated they were going to kick us out of the Society if we didn’t give it up. It has always amazed me that around 1932, the clinic was threatened with expulsion from the King County Medical Society and, four years later, Dr. Mason was president of the American Medical Association.”

[Margaret Edmunds: “Few people could resist liking Dr. Mason. He had a winning personality. When he talked with you, you felt you were the only person on earth he was talking to. Absolutely wonderful. He charmed everyone.”]

“Dr. Lester Palmer was interested in diabetes. He trained under Dr. Elliott Proctor Joslin, the first U.S. physician to specialize in diabetes. He also promoted diabetic camp for Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Dr. Palmer always took a nurse to camp with him to administer insulin, etc. I think he probably paid for all of this out of his own pocket. Lester was the camp doctor and Margaret Brown was the nurse there for a number of years. He later formed The Diabetic Trust Fund between 1938 and 1939.

I was in the lab doing blood sugars on all these little diabetic children when I said to Dr. Mason, “These are the healthiest children I’ve ever seen. Is there something about diabetes that makes their cheeks so rosy and look so well?” He said, ‘No, it’s just the careful care they’ve been having.’ These children looked wonderfully well.”

Margaret Edmunds: Wife of Dr. Louis Edmunds, Hospital Employee in the ’30s

(Excerpted from an interview with Margaret Edmunds and Louis Edmunds, MD, on April 16, 1985.)